As today

is the day that Karl Wallenda's great-grandson Nik will

stroll across a gorge near the Grand Canyon on a cable, safely we

hope, it's the perfect time to recall that Karl walked

across the top of Atlanta Stadium in 1972 between the

games of a doubleheader. Atlanta Braves' promotions

director Bob Hope wrote a superb book in the early 90s

recalling the zany stunts the Braves employed with great

regularity in the 1970s in an attempt to fill seats at the

ballpark. The following is an excerpt from his book

We Could Have Finished Last Without You.

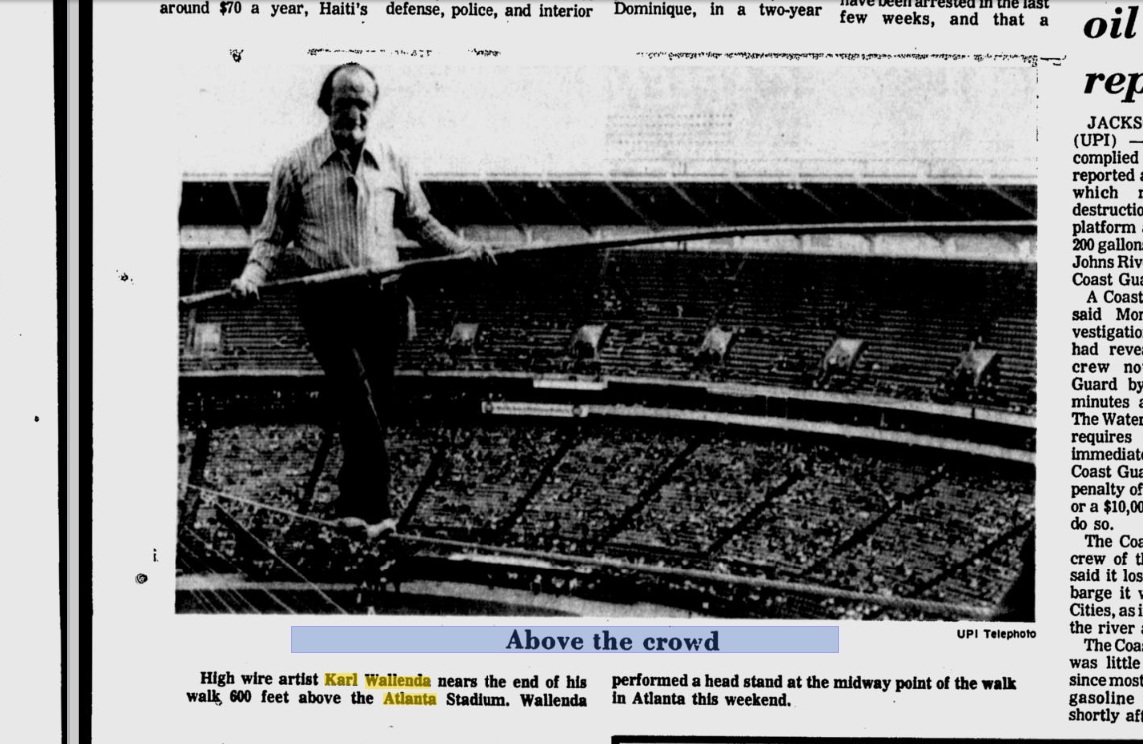

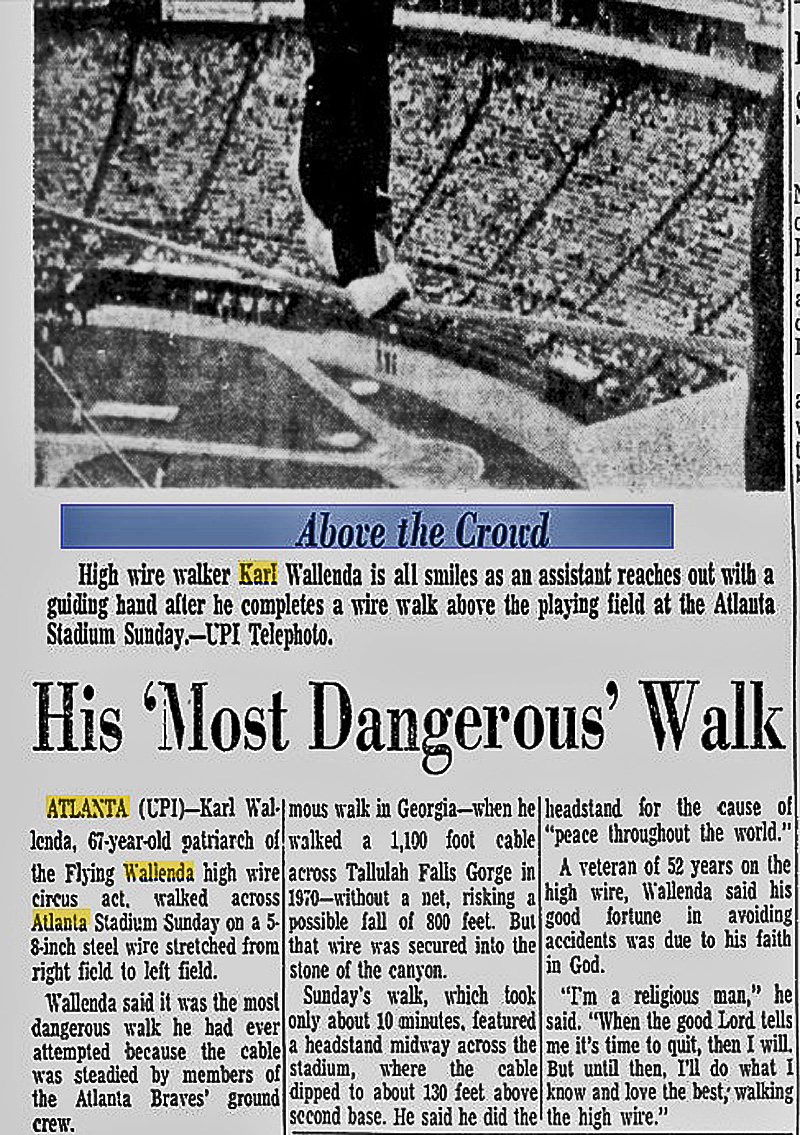

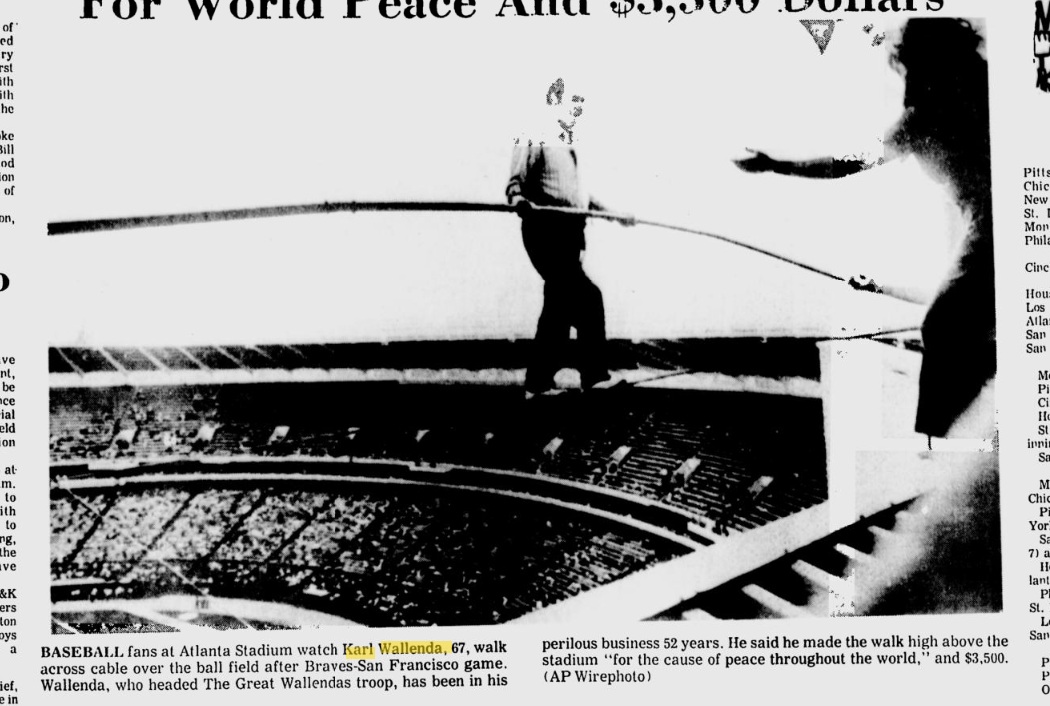

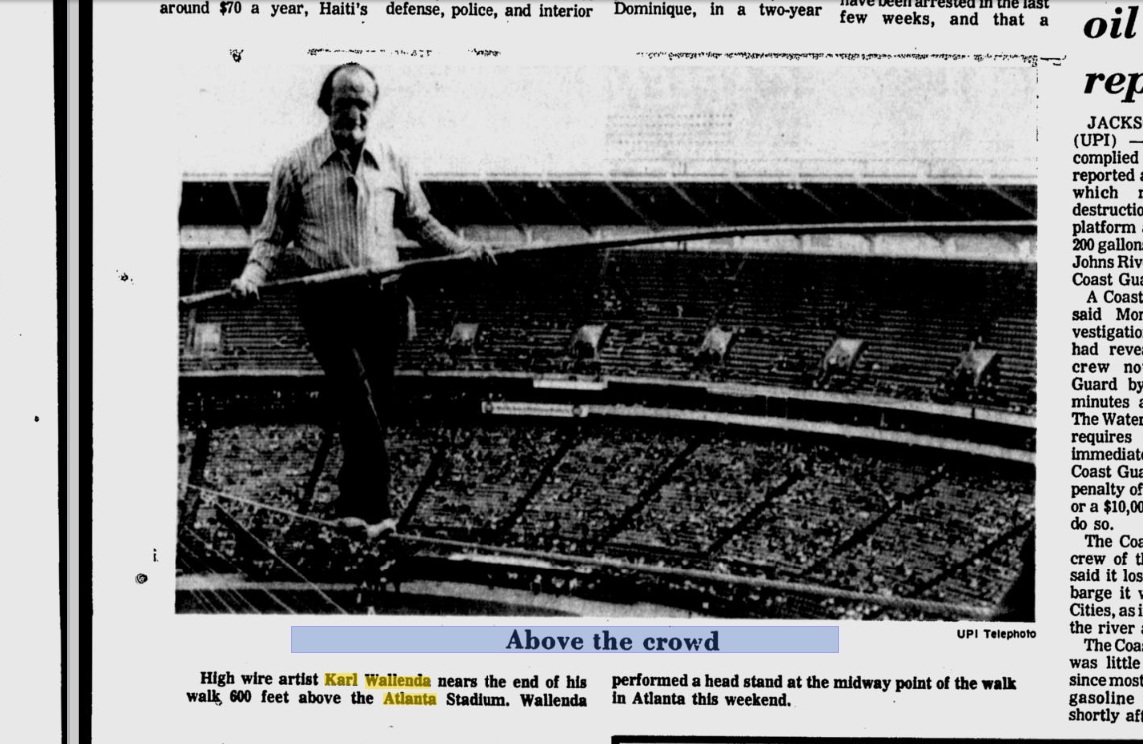

"The Braves games were the perfect setting for anything we wanted to do. We paid the legendary wire-walker Karl Wallenda $3,000 to walk his wire across the top of the stadium between games of a doubleheader. The stunt was the most amazing I could imagine. Basically, the Great Wallenda, as he was called by those who follow wire-walking, drove into town with all his equipment in the back of a truck. He, his niece, and a couple of other family members strung the wire (actually a cable) across the very top of the stadium, spanning over first and third base from the stadium light towers, more than three hundred feet across. Wallenda was in his seventies (the article below says 67 - ATM) but he worked the entire day prior to the walk putting up the contraption.

In fact, the night before his performance Wallenda was so tired that he fell asleep during the game on a sofa in the press lounge adjacent to the press box. Dozing off is likely what any seventy-year-old man who had just been through a day of hard labor might do. But he had taken a few drinks, and rumor swept through the press box that he passed out drunk. The old man, so they thought, was in a stupor, and the next day I was paying him to walk a long thin wire a hundred feet above the ground in a stadium full of people, many of them kids (the article below says 600 feet above the ground - ATM). Everyone assured me he would fall and kill himself in front of all those people. And, of course, it would be my fault.

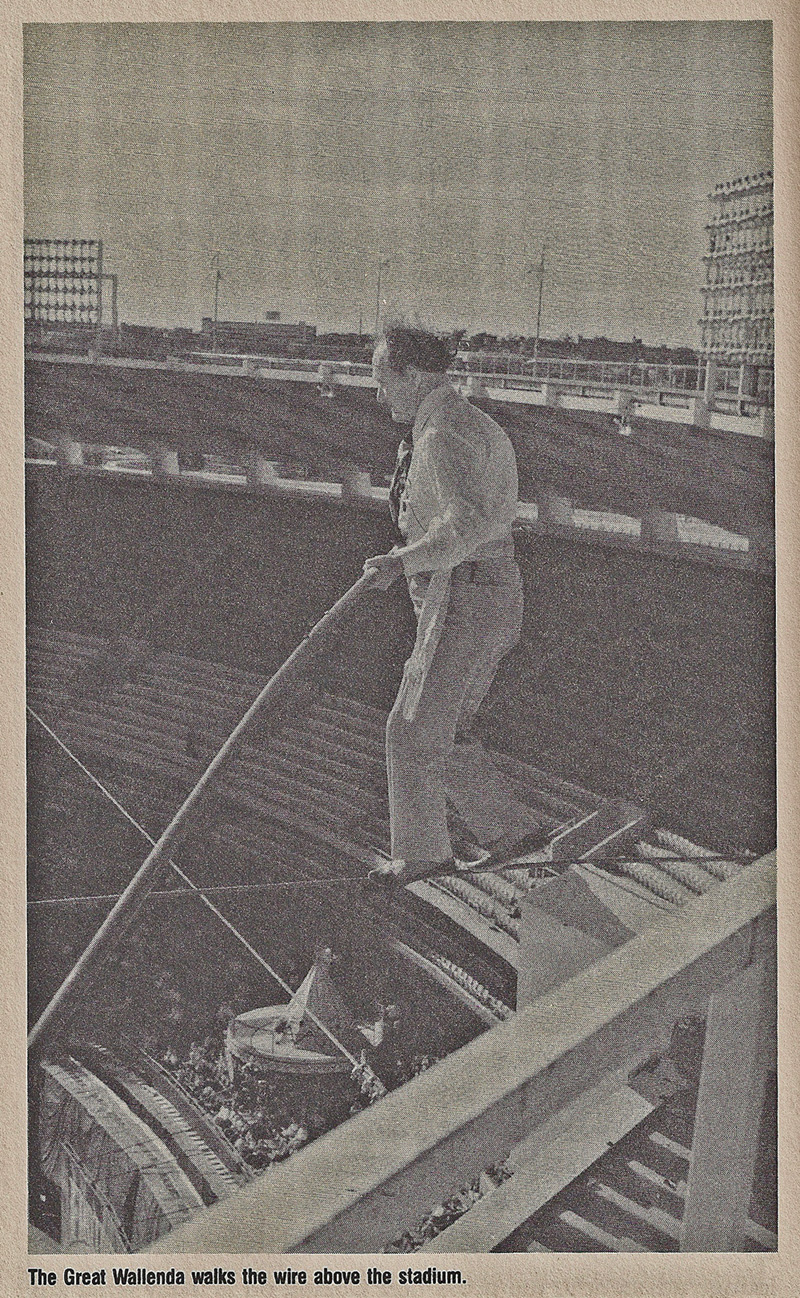

Perplexed, I decided to climb into the lights of the stadium and try to comprehend what Wallenda had in front of him the next day. I wanted to take a close look at the wire Wallenda would have between him and the ground. I'll always remember the moment I stood at the edge of the wire and looked down on the field and crowd below. I tried to imagine what it would take to make him take that first step out onto the wire. The ball game was going on below, and the players looked like little bugs moving around. The crowd was a mass of blurry spots. It was terrifying. No way this could be done.

During the first game of the doubleheader the next day, Ted Turner called me to join him in the seats next to the dugout. "I know winds," Ted said in an obvious reference to his sailing, "and these are the most dangerous kinds. Cancel the old man's walk. Tell him it's too risky."

I tried to talk Wallenda out of walking, but his reputation was at stake. Circus performers are legendary for their determination that "the show must go on."

The whole scenario of the Wallenda walk was deadly. At the end of the first game of the doubleheader, every able-bodied ground-crew member and stadium usher was on the field. They faced each other in two lines parallel to Wallenda's cable, and each one was given the end of one of the many ropes attached to the cable. Each man wrapped his rope-end around his waist twice and knotted it in front, then leaned backward to provide enough tension to keep the cable steady. No one could slip, they were told, or the Great Wallenda would fall.

"Oh, God," I thought to myself, "I've finally killed someone. I've gone too far."

Wallenda, looking every bit his age, stepped onto the cable. The crowd gasped as he walked slowly, holding onto a long balance pole, crossing the stadium a step at a time. Every few steps he would stop and look like he might be stumbling or losing his balance. He would yell instructions down to the ground. But by the mid-point of his walk, I could tell this guy knew what he was doing. On closer look, the uncertain steps looked more act than accident. And in twelve minutes flat, he was all the way across, safe on the other side.

He was an amazing man. Performance was his life, and after that first frightful performance, I had him back to repeat several times."

"The Braves games were the perfect setting for anything we wanted to do. We paid the legendary wire-walker Karl Wallenda $3,000 to walk his wire across the top of the stadium between games of a doubleheader. The stunt was the most amazing I could imagine. Basically, the Great Wallenda, as he was called by those who follow wire-walking, drove into town with all his equipment in the back of a truck. He, his niece, and a couple of other family members strung the wire (actually a cable) across the very top of the stadium, spanning over first and third base from the stadium light towers, more than three hundred feet across. Wallenda was in his seventies (the article below says 67 - ATM) but he worked the entire day prior to the walk putting up the contraption.

In fact, the night before his performance Wallenda was so tired that he fell asleep during the game on a sofa in the press lounge adjacent to the press box. Dozing off is likely what any seventy-year-old man who had just been through a day of hard labor might do. But he had taken a few drinks, and rumor swept through the press box that he passed out drunk. The old man, so they thought, was in a stupor, and the next day I was paying him to walk a long thin wire a hundred feet above the ground in a stadium full of people, many of them kids (the article below says 600 feet above the ground - ATM). Everyone assured me he would fall and kill himself in front of all those people. And, of course, it would be my fault.

Perplexed, I decided to climb into the lights of the stadium and try to comprehend what Wallenda had in front of him the next day. I wanted to take a close look at the wire Wallenda would have between him and the ground. I'll always remember the moment I stood at the edge of the wire and looked down on the field and crowd below. I tried to imagine what it would take to make him take that first step out onto the wire. The ball game was going on below, and the players looked like little bugs moving around. The crowd was a mass of blurry spots. It was terrifying. No way this could be done.

During the first game of the doubleheader the next day, Ted Turner called me to join him in the seats next to the dugout. "I know winds," Ted said in an obvious reference to his sailing, "and these are the most dangerous kinds. Cancel the old man's walk. Tell him it's too risky."

I tried to talk Wallenda out of walking, but his reputation was at stake. Circus performers are legendary for their determination that "the show must go on."

The whole scenario of the Wallenda walk was deadly. At the end of the first game of the doubleheader, every able-bodied ground-crew member and stadium usher was on the field. They faced each other in two lines parallel to Wallenda's cable, and each one was given the end of one of the many ropes attached to the cable. Each man wrapped his rope-end around his waist twice and knotted it in front, then leaned backward to provide enough tension to keep the cable steady. No one could slip, they were told, or the Great Wallenda would fall.

"Oh, God," I thought to myself, "I've finally killed someone. I've gone too far."

Wallenda, looking every bit his age, stepped onto the cable. The crowd gasped as he walked slowly, holding onto a long balance pole, crossing the stadium a step at a time. Every few steps he would stop and look like he might be stumbling or losing his balance. He would yell instructions down to the ground. But by the mid-point of his walk, I could tell this guy knew what he was doing. On closer look, the uncertain steps looked more act than accident. And in twelve minutes flat, he was all the way across, safe on the other side.

He was an amazing man. Performance was his life, and after that first frightful performance, I had him back to repeat several times."